| REHABILITATION

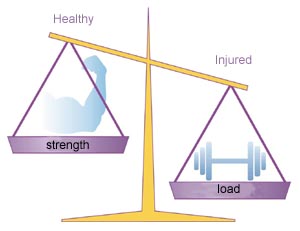

In simple terms, sports injuries occur when the tissue is subjected to a load that exceeds the strength of the tissue. |

|

| The imbalance between the tissue strength (level of training) and the load is vital in understanding sports injuries – partly understanding how the injuries occur and partly how the injuries should be treated or prevented. The risk of the injury (re)occurring is therefore reduced not only by reducing the load or strain, but also by increasing the level of training.

This entails that the damaged tissue (muscle, tendon, ligament, bone) must be relieved, but also that a controlled training of the damaged tissue must be performed so that it becomes even stronger than before the injury occurred. The injured athlete must therefore train general fitness, strength and agility, as well as special training aimed at slowly increasing the strength of the damaged tissue. Injured athletes must therefore train even more than healthy athletes. In some cases the injury is a result of poor equipment (i.e. inferior running shoes), incorrect technique or inappropriate training (i.e. increasing the intensity of the training much too quickly). It is absolutely vital that these conditions are altered, as the injury will otherwise reappear relatively quickly after a training break due to injury. Many sports injuries are caused by over-load due to incorrect (re)training. Four weeks’ training is required in order to have any effect on muscle strength, four months to have an effect on bone strength, and eight months’ training to have any effect on tendon and ligament strength. Rapidly increasing intensity and quantity of training will therefore quickly increase the strength of the muscles, and consequently the load the muscles transfer to the tendons and bones. The tendons and bones are, however, not as yet fully trained to manage the increased load resulting in over-load symptoms from the bones (i.e. inflammation of the shin bone (shin-splint), stress fracture), or the tendons (i.e. inflammation of the Achilles tendon, groin, hollow foot tendon, knee cap tendon etc.). To guard against over-load injuries, the training quantity and intensity must be increased so slowly that the muscles, bones and tendons can all adjust to the increased load. When the tissue is damaged, this usually entails bleeding and release of fluid in the tissue thereby causing pain. Acute injuries can result in such heavy bleeding that swelling and pain quickly appear. Injuries from over-load usually entail such moderate bleeding and release of fluid in the tissue that tenderness often does not develop for the first few hours (appearing in the evening or next morning). This tenderness is however an important signal that the tissue has been subjected to a greater load than it is trained to manage, and that some damage has (re)occurred. It is often only necessary to undergo a few days’ relief and special training to make the symptoms disappear if training is immediately adjusted. If training is not adjusted the over-load will continue and the injury will, over the course of days to months, develop into a prolonged and in worst case chronic injury, which will render sports activity impossible for months or years. It is therefore absolutely vital that the athlete learns to listen to the body’s signals and adjusts training as soon as pain arises. All rehabilitation should be performed within the pain threshold. Rehabilitation of sports injuries is divided into two parts: Part 1 comprises relief of the damaged tissue (tendon, ligament or muscle) as long as there is swelling or pain in evidence. It is important to avoid total breaks in training, and training of all muscles and joints which are not injured should be continued. It takes much longer to build up tissue than to break it down, and it can therefore take several months to build up form again after “three weeks’ break”. All breaks in training weaken all muscles, tendons, ligaments and bones, which means that there is a considerable risk of incurring injury when training is commenced once again. Whilst the athlete is resting the damaged tissue, the following can by and large always be continued:

This type of relief is termed “ACTIVE REST”. Part 2 comprises a specific rehabilitation of the damaged tissue, with the aim of making the tissue so strong that it can manage the required load. To reduce the risk of a relapse of the injury it is necessary for the tissue to be even stronger than prior to the injury breaking out. The specific rehabilitation should be commenced 24-48 hours after the injury has occurred (so as not to risk the bleeding becoming worse). Medicinal treatment does not advance the course of Part 2 of the rehabilitation, as no legal substances will be able to increase the tissue’s strength. This can only be achieved through sensible training. |

|