TAPING

Prepared by Finn Johansen, specialist in rheumatology, in co-operation with Norvartis Healthcare A/S.

In an attempt to relieve the damaged structures, special tape (often termed “sports tape”) can be attached on the skin.

Taping is especially used on sprains, with the following purpose:

1. Primary prevention to protect healthy tendons in particular loads where there is risk associated.

2. Acute treatment after a sprain to avoid further injury of the damaged tendon.

3. Rehabilitation after a sprain to control the load, and thereby accelerate the healing process.

4. Secondary prevention to avoid new sprains during the rehabilitation period (3-6 months), and during a possible subsequent chronic excessive laxity of joint condition.

Taping can also be utilised for relief of over-loaded structures, such as:

1. Bones, i.e. in cases of stress fractures (metatarsus stress fracture).

2. Tendons, i.e. in cases of inflammation of the hollow foot tendon (fasciitis plantaris).

Taping is furthermore used to correct malalignment (bio-mechanical correction):

1.Kneecap stabilisation for pain around the kneecap triggered by faulty kneecap alignment (patella malalignment).2. Elbow stabilisation to avoid pain triggered by over-stretching (hyper-extensions)

3. Fatty-pad stabilisation for pain under the heel triggered by a degenerated fatty-pad.

4. Secondary prevention to avoid new sprains during the rehabilitation period (3-6 months), and during a possible subsequent chronic excessive laxity of joint condition.

General principles for taping:

1. Shave the hairs where the tape is to be applied. The tape will thereby attach more securely, and be less painful to remove.2. Wash and dry the skin thoroughly prior to application, to enable the tape to attach more securely.

3. Tape can better attach itself to tape than to skin. It is therefore often advisable to set circular strips of tape as “anchors” and “locks”.

4. Tape which is attached around the arms or legs should be elastic, and loosely applied whilst the underlying muscles are taut.

5. The tape should be applied smoothly, without folds, thereby enabling the tape to attach more securely and reduce the risk of blister and skin irritation.

6. The width of the tape should be chosen in proportion to the structure to be taped. As a general rule, the tape should be 2.5 – 3.5 cm wide.

7. As little tape as possible should be used, and tape application which compromises normal mobility should be avoided, unless of course, this is the aim of the taping.

8. Rub the tape thoroughly when applied, as the tape will attach more securely when warm.

9. If there are problems with the tape becoming loose, spraying with liquid plaster or adhesive spray can be attempted before applying the tape.

10. Be aware that old tape, or tape which has been subjected to strong heat, will lose some of its adhesiveness.

11. The tape should be carefully separated from the skin when removed to reduce possible skin irritation.

12. Prolonged use of tape can often result in skin irritation and possible allergic reactions.

Specific taping:

1. HEEL PAD

2. HOLLOW FOOT TENDON

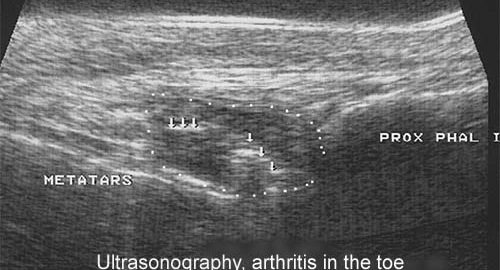

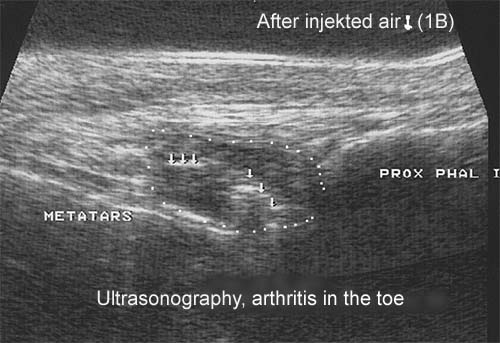

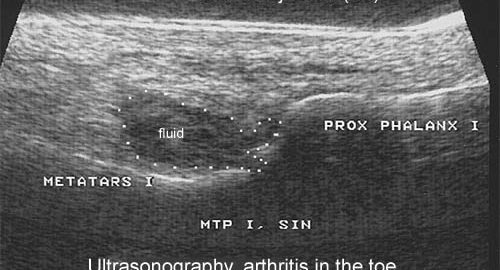

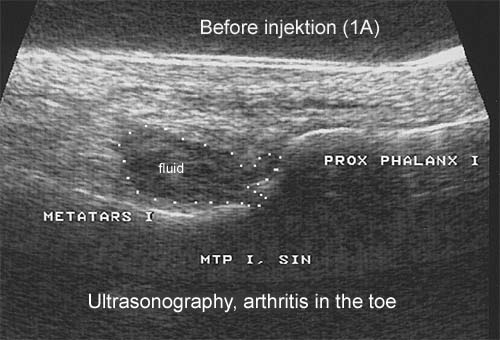

3. BIG TOE

4. METATARSUS

5a. ANKLE TAPE, STIRRUP

5b. ANKLE TAPE, ANKLE LOCK

5c. ANKLE TAPE, FIGURE-8 BANDAGE

5d. ANKLE TAPE, DOUBLE FIGURE-8 BANDAGE

6. KNEE, LATERAL STABILISATION

7. KNEE STABILISING BANDAGE

8. ELBOW SUPPORTING BANDAGE

9. THUMB BANDAGE

10. FINGER TAPE

11. ACHILLES TENDON

12. TOE NAIL

13. TENNIS ELBOW & GOLF ELBOW

14. JUMPER’S KNEE