|

The effect of preventive measures on the incidence of ankle sprains. DATA SOURCES. STUDY SELECTION. DATA EXTRACTION AND SYNTHESIS. MAIN RESULTS. CONCLUSIONS. |

Kategoriarkiv: Ligament injury in the ankle joint, outer ligament

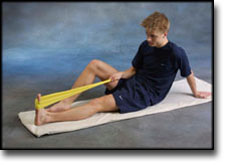

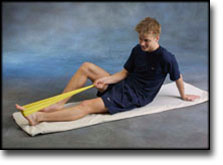

Special(seesaw exercise)

|

Seesaw. Balance on two legs, possibly using a hand as support against the wall, balancing subsequently on one leg without support. Look straight ahead and keep knees bent. |

|

complication-article1

|

Limited dorsiflexion predisposes to injuries of the ankle in children. |

complication-article1

|

Chronic recurrent ligament instability on the lateral ankle. |

STEP4

TRAINING LADDER FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS:

FOR INNER LIGAMENT INJURY IN THE ANKLE JOINT

(RUPTURA TRAUMATICA LIGAMENTI LATERALIS PEDIS)

Unlimited: Cycling. Swimming. Running with directional change.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stretching is carried out in the following way: stretch the muscle group for 3-5 seconds. Relax for 3-5 seconds. The muscle group should subsequently be stretched for 20 seconds. The muscle is allowed to be tender, but must not hurt. Relax for 20 seconds, after which the procedure can be repeated.

The time consumed for stretching, coordination and strength training can be altered depending on the training opportunities available and individual requirements. |

STEP3

TRAINING LADDER FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS:

FOR INNER LIGAMENT INJURY IN THE ANKLE JOINT

(RUPTURA TRAUMATICA LIGAMENTI LATERALIS PEDIS)

Unlimited: Cycling. Swimming. Running straight ahead (without directional change).

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stretching is carried out in the following way: stretch the muscle group for 3-5 seconds. Relax for 3-5 seconds. The muscle group should subsequently be stretched for 20 seconds. The muscle is allowed to be tender, but must not hurt. Relax for 20 seconds, after which the procedure can be repeated.

The time consumed for stretching, coordination and strength training can be altered depending on the training opportunities available and individual requirements. |

STEP2

TRAINING LADDER FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS:

FOR INNER LIGAMENT INJURY IN THE ANKLE JOINT

(RUPTURA TRAUMATICA LIGAMENTI LATERALIS PEDIS)

Unlimited: Cycling. Swimming, Light running straight ahead (without directional change) on a smooth surface.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stretching is carried out in the following way: stretch the muscle group for 3-5 seconds. Relax for 3-5 seconds. The muscle group should subsequently be stretched for 20 seconds. The muscle is allowed to be tender, but must not hurt. Relax for 20 seconds, after which the procedure can be repeated.

The time consumed for stretching, coordination and strength training can be altered depending on the training opportunities available and individual requirements. |

STEP1

TRAINING LADDER FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS:

FOR INNER LIGAMENT INJURY IN THE ANKLE JOINT

(RUPTURA TRAUMATICA LIGAMENTI LATERALIS PEDIS)

Unlimited: Cycling. Swimming.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stretching is carried out in the following way: stretch the muscle group for 3-5 seconds. Relax for 3-5 seconds. The muscle group should subsequently be stretched for 20 seconds. The muscle is allowed to be tender, but must not hurt. Relax for 20 seconds, after which the procedure can be repeated.

The time consumed for stretching, coordination and strength training can be altered depending on the training opportunities available and individual requirements. |

bandage-article2

|

Interventions for preventing ankle ligament injuries. OBJECTIVES. SEARCH STRATEGY. ELECTION CRITERIA. DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS. MAIN RESULTS. REVIEWER’S CONCLUSIONS. |

bandage-article1

|

The prevention of ankle sprains in sports. A systematic review of the literature. |