| Cause: The bursas can become inflamed, produce fluid, swell and become painful with repeated over-load or due to blows. Although the condition is termed inflammation of the bursa, there is not often an infection in the bursa.

Symptoms: Pain when applying pressure to the bursa, which sometimes, but far from always, can give the impression of being swollen. The pain is aggravated when the muscle above the bursa is activated.

Acute treatment: Click here.

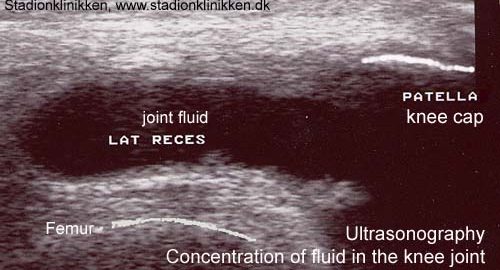

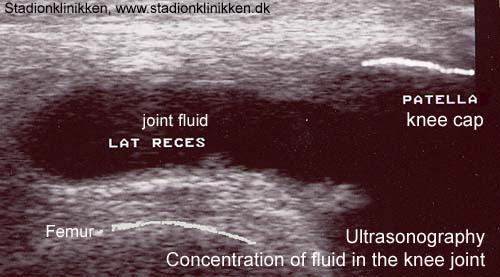

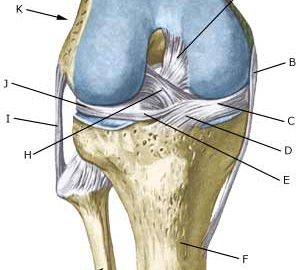

Examination: Medical examination is usually not required in light cases with only minimal tenderness. With more pronounced pain, or lack of improvement, medical examination should always be performed to confirm the diagnosis and commencement of treatment if required. The diagnosis is usually made from a normal medical examination, however, if any doubts arise an ultrasound scan can be performed which is most well suited to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment: Treatment is primarily concentrated on providing rest. Treatment can be supplemented with rheumatic medicine (NSAID) or injection of corticosteroid in the bursa preceded by draining, which can be best performed under ultrasound guidance (article).

Rehabilitation: Treatment is completely dependent upon which bursa is inflamed, but the sports activity can usually be cautiously resumed when the pain has diminished, especially if the provoking factor has been identified and removed.

Also read rehabilitation, general.

Complications: If there is not a steady improvement in the condition consideration must be given as to whether the diagnosis is correct, or if complications have arisen:

In rare cases, the bursa can be infected with bacteria. This is a serious condition if the bursa becomes red, warm and increasingly swollen and tender. This condition requires immediate examination and treatment. If relief and medicinal treatment (including ultrasound guided injection of corticosteroid) does not produce any progress, a surgical removal of the bursa can be attempted.

Special: Shock absorbing shoes or inlays will reduce the load. If there is a lack of progress or a relapse after successful rehabilitation, consideration must be given to performing a running style analysis to establish whether a correction of the running style should be recommended.

|