NSAID (rheumatism medicine)

Use of NSAID is widespread in sport as a painkiller, and as treatment to subdue inflammation.

Indication. Over-load symptoms from tendons. A considerable number of scientific studies have been performed comprising NSAID treatment on acute tendon injuries. In the majority of studies, but not all, healing was achieved slightly quicker, and inflammation was slightly reduced compared with placebo treatment. Some studies have shown increased instability and reduced mobility in the joints after NSAID treatment.

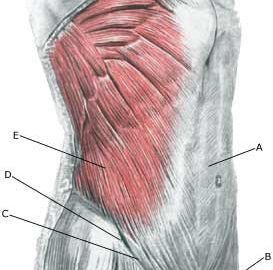

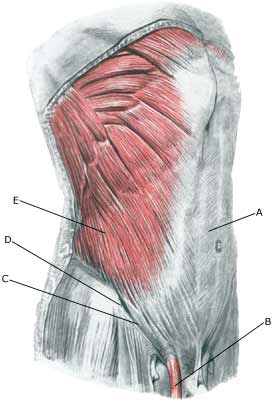

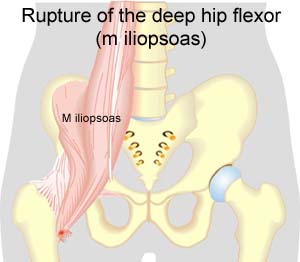

Acute muscle injuries. There are only a handful of animal studies dealing with NSAID treatment of acute muscle injuries. Increased muscle strength has been proven, however, also reduced healing of damaged tissue.

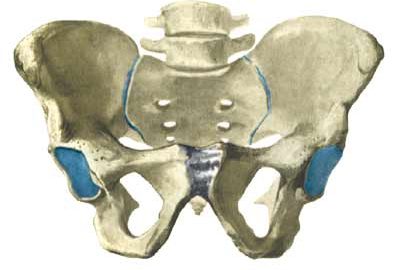

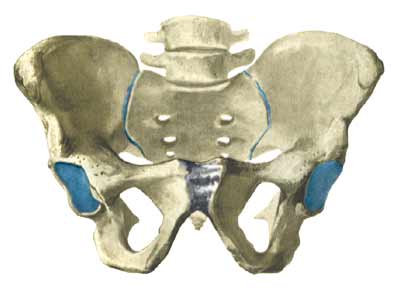

Myositis ossifans (calcification in muscles after bleeding). One study shows that calcification in the muscles following a hip operation is reduced in patients who are treated with NSAID after the operation.

Chronic muscle and tendon injury. There is no conclusive scientific evidence supporting use of NSAID on chronic muscle or tendon injuries.

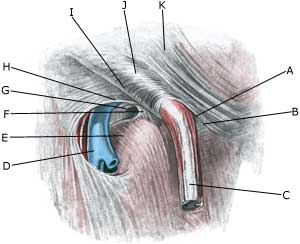

Side effects. Side effects from the abdomen and intestines (heartburn, gastric ulcer and sour eructation) are frequent following treatment with NSAID. The new rheumatism pills (“selective COX-2 inhibitors”, as for example, Vioxx) are by and large free of serious side effects from the abdomen and intestines. Serious side effects are rare, but allergic shock, kidney damage and bone marrow damage has been described. Only moderate side effects are seen following localised treatment with NSAID (allergy).

Contraindications. Allergy is on the whole the only contraindication for NSAID treatment in healthy athletes. Patients with gastric ulcer, high blood pressure, liver, heart and kidney illnesses should be cautious with NSAID treatment.

Administration. Tablet treatment is recommended. Some placebo controlled studies show that local NSAID as gel is better than placebo on acute injuries, despite the concentration of blood following localised treatment constituting less than 10% of the level after tablet treatment or after injection in the muscles. There are no scientific grounds for using injection methods. There are no studies which document the ideal point in time to start NSAID treatment, or the length of duration.

Discussion. There is no conclusive clarification as to whether inhibiting the acute inflammation is an absolute advantage. Pain and discomfort are in any event partially conditional upon the inflammation. By reducing the inflammation the symptoms are reduced, thereby allowing rehabilitation to start at an earlier stage. On the other hand, the inflamed cells are responsible for the decomposition of the tissue which has been destroyed, which is necessary for removal of dead muscle fibre and the like.

Conclusion. Several clinical studies have documented that treatment with NSAID has some effect on sports injuries. There are, however, still many unanswered questions preventing a sure, unequivocal indication for treatment with NSAID to be given. If systematic NSAID treatment is indicated, the new rheumatism pills (“selective COX-2 inhibitors” for example Vioxx), can be recommended. As mentioned above, NSAID treatment is merely a supplement to the base treatment which is “active rest” with increasing intensity in training within the pain threshold. If NSAID is misused as a painkiller to continue a potentially damaging sports activity, the treatment will indirectly increase the risk of the chronic injury. It is for this reason that all NSAID treatment on athletes must be administered by a physician with knowledge of the basic rehabilitation principles.